Biography

Raya Buensuceso is the managing director of Kaya Founders, a venture capital firm based in Manila. Kaya backs pre-seed to Series A startups in the Philippines and Southeast Asia. Kaya recently raised a $25M fund, its second one so far.

Outside of Kaya Founders, Raya is the chapter lead of SoGal Foundation, a global nonprofit committed to the empowerment of female and other underrepresented entrepreneurs/investors. She has also worked for the Milken Institute, an economic think tank, and Polestrom, a boutique consulting firm.

Some of Kaya Founders’ notable investments include Etaily (e-commerce enabler), PayMongo (payment gateway), and Peddlr (mobile PoS for small businesses).

Why does Kaya refer to the Philippines as “underserved and underinvested”?

Indonesia attracts investors with its massive TAM, while Singapore benefits from ease of doing business, strong talent pools, and higher purchasing power. Both markets have enjoyed early breakout successes like Grab, Sea Group, and Gojek. These markets built proof points early, while the Philippines is still catching up.

I’ve been involved in the local startup ecosystem for nearly a decade. For years, the Philippines has lacked real exits and role models. Coins.ph’s $72mn acquisition by Gojek (in 2019) was the ecosystem’s largest exit, which is small relative to regional peers. This delayed the compounding of talent, capital, and repeat founders.

Local capital was also limited. Early investors were mostly government-funded accelerators and traditional conglomerates that didn’t quite understand VC norms. They invested in companies but took large equity chunks, which made startups “uninvestable” for later VCs. Some would offer investments in the form of credits or grants (of ~$10k). These evidently weren’t enough to help startups scale.

This has improved thanks to more sophisticated CVCs such as JG Dev and Kickstart that invest in the Philippines and across SEA, as well as new independent funds—including Kaya—that have since set up shop.

Today, with Indonesia slowing and investors searching for differentiated alpha, regional attention is shifting toward the Philippines and Vietnam. Rocket Internet-led companies like Lazada, Zalora, and Grab have grown here, seeding talent and inspiring a new generation of Filipino founders.

Our own partners were products of the Rocket Internet mafia, having previously co-founded Zalora (Paulo Campos) and led Lazada’s Philippine business (Ray Alimurung). The Filipino ecosystem currently sits at a nice junction.

What is the Filipino market’s strength?

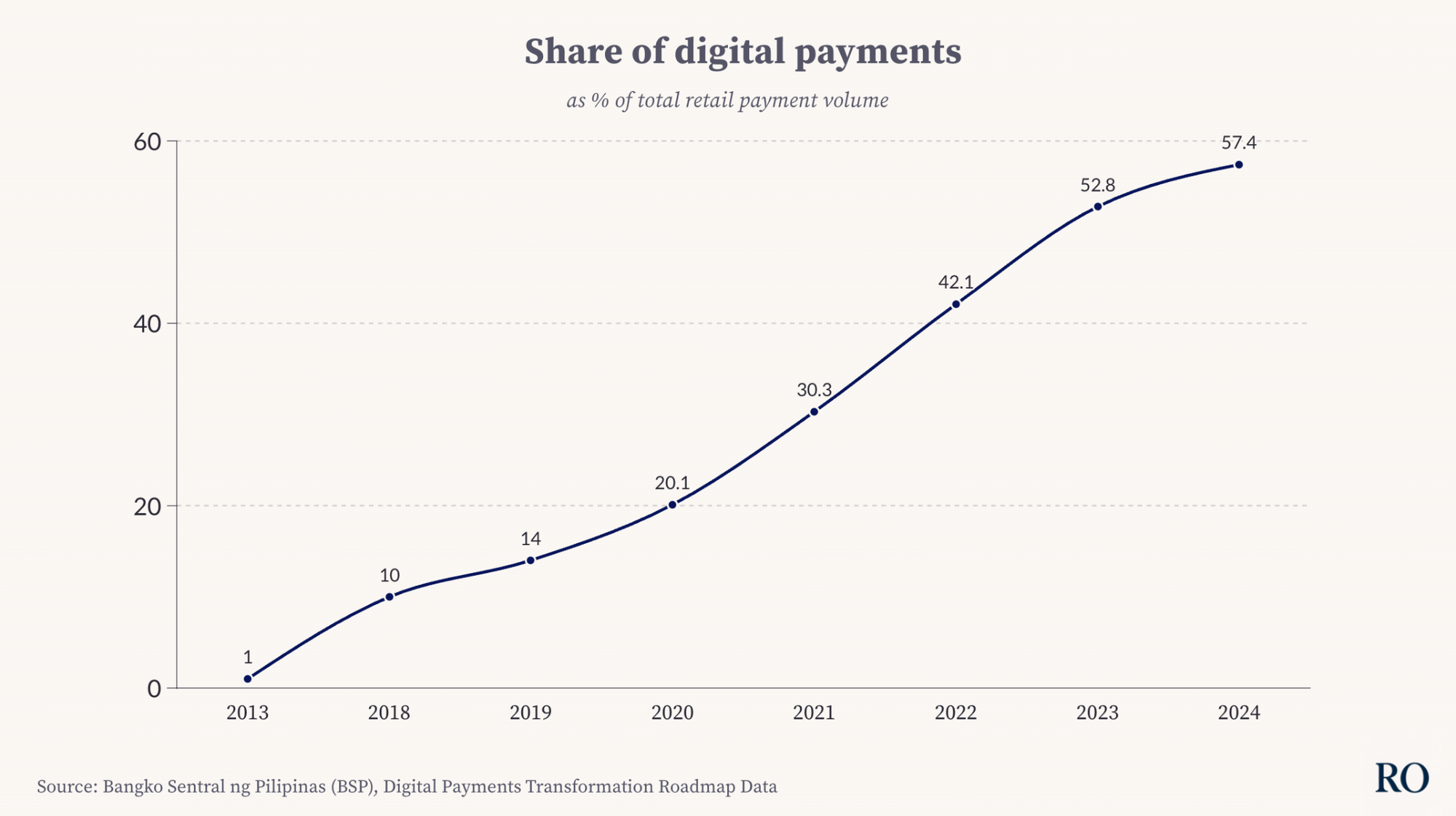

The Philippines has strong digital momentum.

The pandemic accelerated the adoption of digital payments, for example. Companies like GCash (a fintech app for sending and receiving money, paying bills, etc.) exemplify this new behavior. The pandemic also increased local businesses’ openness to tech solutions.

Source: Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (the Philippines’ central bank) report

This growth is compounded by other market characteristics.

First, the Philippines is one of the world’s most active social-media markets, making consumers digitally savvy and early adopters of new tech products.

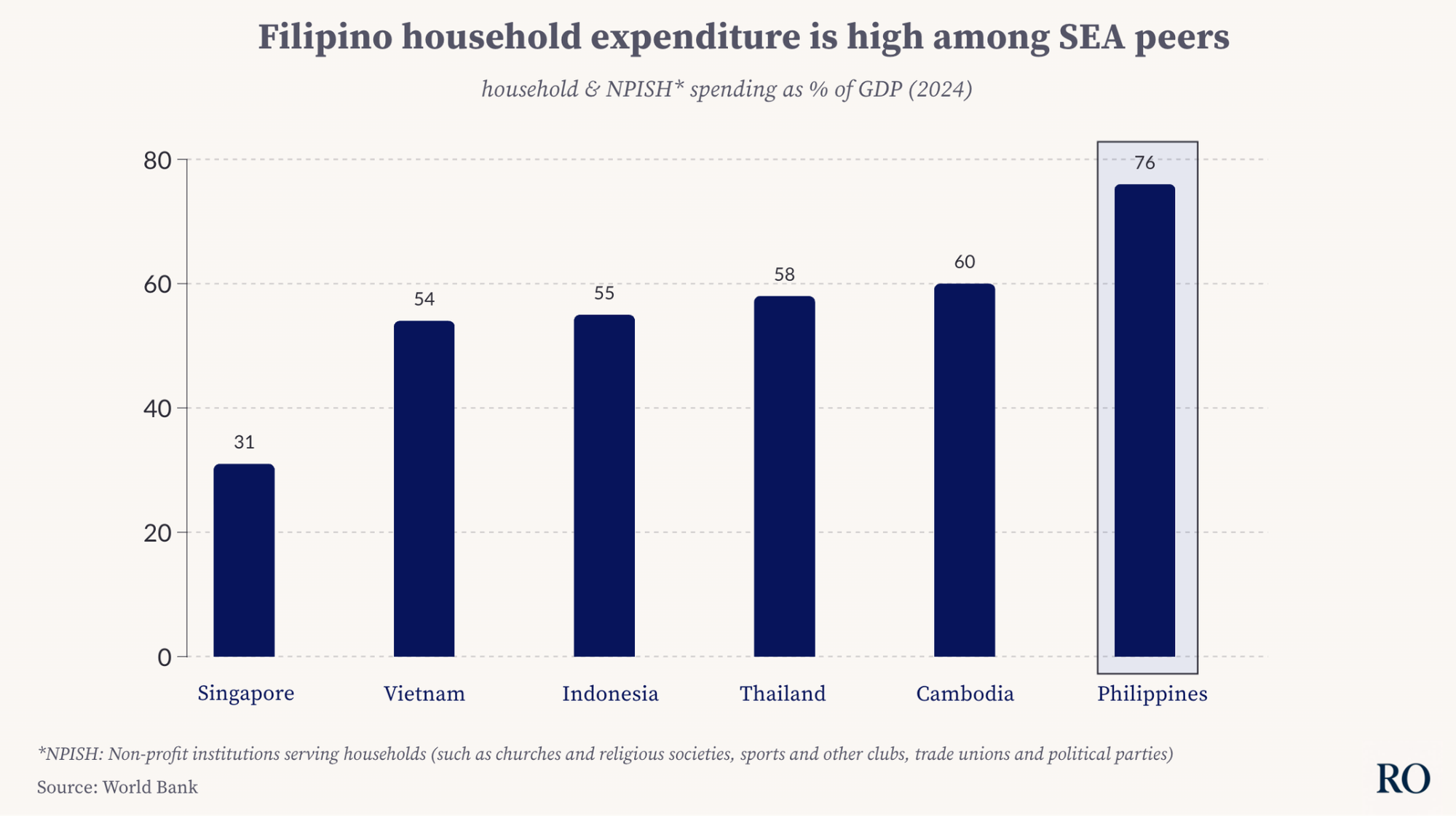

Second, the economy is heavily consumer-driven, with household spending accounting for about 75% of GDP.

Third, the population is young, with an average age of around 25, much younger than peers like Vietnam and other SEA countries.

How have you “segmented” the Filipino consumer?

The Filipino government uses a consumer classification based on income levels. It segments consumers from A (high income) to E (low income). For us, as investors, only consumers in the A, B, and C1 and C2 segments are realistically monetizable. These are consumers with sufficient spending power.

Aligned with Lightspeed’s 2024 report, we split Filipino consumers into two meaningful segments: convenience-focused A and B power users, and value-focused mass-market consumers.

For startups, this creates two viable pathways to build a meaningful business. Startups can either build for the top ~5% or for the mass market. But “the mass market” in the Philippines has very different spending power from the mass market in the US or China.

Some industries, and the different companies serving them, illustrate this difference.

In coffee, the premium option is the $3 per cup Starbucks, while the mass-market equivalent is something like Pickup Coffee, which sells coffee at $1 per cup. In mobility, Grab costs $4–10, while motorcycle taxis like Angkas are closer to $1. You can build for either segment, but the key is aligning price points and unit economics.

We have made investments in both kinds of businesses.

On the premium side, we have a company called Kindred, a women’s health clinic network. They opened their first branch in Fort Bonifacio (a premium Central Business District outside Manila). Now, they’re looking to expand across the country, with 10 clinics and counting. Their customers generally fall within the A and B classes. Looking at future plans, they’re focused on capturing a larger share of these women’s “health span” by expanding beyond tele-consults and HPV vaccines into services like maternity care and beyond.

On the mass-market side, we have Tomo Coffee, a coffee company that’s similar to Pickup Coffee. They’re priced at around $1–2 (50–100 pesos), and located in hospitals, schools, transit hubs, and BPOs, rather than business centers. Their mass positioning is clear.

Source: World Bank

RO insights: women's health startups and the necessity of multi-product

Women’s health startups generally start by providing a specific service. To be venture-scale though, these startups likely have to expand into adjacent services.

Here’s how Stephanie von Staa Toledo, founder of Brazilian women’s health startup Oya Care, explains:

“In the context of women’s health, the concept of a “minimum viable portfolio” makes more sense than a “minimum viable product”. We estimate that 80% of Brazilian women go to the doctor once a year. This is good for their health, but not a frequency on which you can build a company.

To increase the frequency with which women interact with Oya, we thus need to offer different services, which women might use throughout the year. This creates a healthier average ticket per patient. However, we can only offer services that complement each other, to avoid pushing patients into services they don’t need.

Fertility assessments were our first product, but they weren’t enough from a business standpoint. We then launched gynecology consultations, both online and in physical clinics. Today, most of our revenue comes from fertility procedures such as egg freezing.

Offering these services allows us to build comprehensive gynecological and fertility assessments for our patients, improving the way in which we can accompany them.”

Excerpt from Oya: bettering women’s health in Brazil, originally published in The Realistic Optimist

As an investor, do you prefer an industry/segment in particular?

We’re generally sector-agnostic. We’ve invested in both B2B and B2C, across sectors ranging from e-commerce, fintech, healthcare, agritech, and more.

I’d love to be investing in pure play SaaS or AI companies. However, the Philippines (and many parts of Southeast Asia) have rudimentary problems that need to be solved first. This requires hybrid, offline-to-online solutions. On the tech side, what we are looking for is the insightful application of technology. Ultimately, what we care about is the potential size of the prize.

Let me tie this back to our earlier conversation. More specifically why, when looking at B2C opportunities, it matters that founders clearly define which consumer segment they’re targeting.

If you’re a founder building a premium offering for the top 5%, the Filipino market alone is usually too small so you need a regional plan. But if you’re targeting B and C segments in a sector such as fintech, the domestic TAM could be large enough to go deep locally.

We’re less discerning about the specific industry than we are about the size of the opportunity.

What are some of your observations from the consumer investments you have made?

First, consumer is often very competitive. These startups require lots of capital to compete, not just with local brands but also with foreign brands entering the market.

Second, channels have shifted. Our best-performing consumer companies sell mostly on TikTok. Two of those companies were started by Chinese founders. One of them, Esse Vida, used to work for TikTok Shop in the Philippines. Based on their insights, they started a brand builder that now creates nutrition and supplements brands sold almost exclusively on TikTok. The other is ecora, a Lululemon-style athleisure company with a large share of its GMV from TikTok.

When we invest in D2C brands now, it’s important that founders truly understand how shopping behavior has evolved. We previously did a few deals where founders came from large corporates. They were comfortable spending big budgets on branding and traditional activations, which aren’t as “hard-working” as online marketing on newer channels.

Third, price point matters. In beauty, for example, we realized there’s a cap on how much you can really charge (roughly around $8 per product). Anything beyond that is hard to sell locally.

Fourth, the ability to iterate and test ideas quickly is crucial. Previously, we might have indexed more on superficial aspects like branding. Now, we know that branding is table stakes, but it isn’t the differentiator. Many of the best-performing D2C brands don’t have the nicest branding. Some look surprisingly basic. But they understand the channels, the algorithms, and what messaging resonates locally.

Source: Kaya Founders’ internal slides

Can you expand on Kaya’s investment themes for 2025?

We have three themes. Each theme corresponds to a structural trend we’re observing.

The first is frictionless business. Here we look for B2B platforms, many now AI-powered, that are transforming the country’s largest industries. The underlying trend we’re tapping is the digitization of business behavior. When we talk to local businesses (including some of our LPs) we see an ongoing generational shift in leadership to the younger generation, who are more willing to explore and adopt tech solutions. This makes B2B, localized startups relevant.

The second theme is the new Filipino consumer. Here, we look at companies building tech-enabled solutions to augment consumers’ convenience, both at the individual and household levels. As previously stated, the Philippines is a consumer-driven economy with high household consumption. Hence, a market where consumer appetite is strong.

The third theme is embedded credit. We like fintech in general. But if you look at fintech in Southeast Asia, the main revenue driver is lending, both in the B2B and B2C segments. We feel there’s still a huge credit gap in the country, even though some of the country’s biggest startups (BillEase, Salmon) are already serving that gap. As more transactions move online, embedded models give lenders access to richer, real-time behavioral and cash-flow data. This engenders better underwriting in a market where data from traditional credit bureaus is paltry.

RO insights: localized AI in SEA

Raya mentioned that investing in “pure tech” plays in a market like the Philippines might not be pertinent. Hybrid, offline-to-online models make more sense.

For SEA founders building in AI, a similar mentality applies. The way in which they build must be contextually-relevant. Building advanced tech for the sake of advanced tech is a flawed approach.

Here’s how Eugene Teo, an investor at Antler, sees that AI localization play out in practice:

“SEA is different from its Western counterpart in terms of enterprise software adoption. People here have skipped multiple technological advancements. For instance, they skipped computers for mobiles, landlines for cellular, and credit cards for digital wallets.

Many businesses here still run on legacy ERPs without APIs, with workflows built around WhatsApp, spreadsheets, and desktop tools. Founders must build around those realities, leading to a new class of “invisible enterprise software” that layers intelligence on top of existing systems instead of replacing them.

Instead of forcing behavior change, startups integrate with what users already use. WhatsApp as the interface, and MCP (Model Context Protocol) connectors as the intelligence layer. This allows instant deployment, minimal training, and fast value realization. What takes months in traditional SaaS can be done in days, with far better CAC-to-LTV dynamics. Companies like Zolo and Civils AI show how this model can scale across industries. This makes enterprise software in SEA not just more accessible, but more efficient and globally instructive.

This approach lowers adoption barriers, because companies and users already have the base software. It also reduces reliance on manual labor, especially at the training level. What once took a team of 20 to 30 people to re-enter data can now be streamlined into a software-driven workflow. The result is enterprise tools that are lighter, cheaper, and more adaptive.”

Excerpt from Southeast Asia tech predictions, by Antler, originally published in The Realistic Optimist

What are you looking for in companies?

We screen for six traits:

- Key insight or contrarian viewpoint. Is there a non-obvious insight the founders are building around?

- Market. Is the market big enough to generate a venture-scale return? Is the market growing? Is there room for a new player to capture value?

- Team. Founder–market fit is incredibly important for us. Is there a personal connection between the founder and the problem? Do they have the domain expertise needed to build a solution in that industry? Do they have grit? Can they execute?

- Traction. We look for some proof of concept that indicates early signs of PMF. Even if there’s no revenue, we want some proof that customers are willing to pay.

- Tech. Is the tech 10x better than the status quo? Is there an insightful application of technology, not tech for tech’s sake, but tech used appropriately for the problem being solved?

- X-factor. This is more nebulous. The x-factor could be IP, a regulatory advantage (like a hard-to-obtain license), a “repeat founder” profile, a strategic partnership that gives them distribution, or anything else that sets the team apart.

What broader Southeast Asian trends do you expect will impact the Filipino market?

A development we’re following is SGX’s (Singapore’s stock exchange) recent tie-up with Nasdaq. The partnership lets eligible companies use a single set of offering documents to list on both exchanges, reducing regulatory friction, cost, and time to access investors in the U.S. and Singapore.

The thorniest question we get from LPs is whether venture capital as an asset class can work in Southeast Asia, given the paucity of large tech exits. We’re closely tracking whether Singapore can crack this. If SGX becomes a viable exit pathway, that will provide real listing options for Filipino startups as well.

You recently raised a $25 million fund. What’s the fund’s focus and mandate?

This fund is split into two smaller funds.

We have a $5 million pre-seed fund called the “Zero-to-One” Fund, and a larger Seed–Series A “One-to-Ten” Fund, which is $20 million. We refer to them together as Fund II, but they’re technically two funds.

These funds will invest across the three themes we just spoke about. We’re already halfway deployed. So far, about half is in frictionless business, 20% in embedded credit, and 30% in the new Filipino consumer.

We’re sector-agnostic and geography-specific. We look at startups relevant to the Philippines, whether they’re based here, founded by Filipinos, or foreign but wanting to expand into the country. We’ve invested in a couple of companies that operate here but cater to foreign markets.

For example, we’ve invested in Edge Tutor, which supplies English and math tutors to tutoring centers in the US, Europe, etc. They’re leveraging the cost arbitrage of teachers here being cheaper, while foreign markets are willing to pay more for their services. We have another company called First Mate Technologies, an AI-powered dev agency for US AI companies, many of them YC-backed. One founder is Filipino, and both are based in Asia, but their clients are entirely in the US.

The sectors we’re less likely to invest in include deep tech and speculative crypto. We’ve done some crypto deals, and we might look at things in the stablecoin space, but nothing overly speculative.

Overall, it’s the same focus we’ve had since we were founded: early-stage, Philippine-focused, across the aformentioned three themes.

What excites your LPs most about the Philippines and Southeast Asia?

We have two types of LPs. Each has their own reason to invest in this market.

On one hand, we have local family offices that are looking to learn more about the startup space. They see us as a way to stay in touch with new trends. There’s also a “nation-building” element to their involvement. They see this as a way to give back and help drive national economic development.

On the other hand, we have foreign investors. These include Pavilion Capital, an offshoot of Singapore’s Temasek, as well as a couple of other global investors. For them, we essentially act as an index fund for early-stage Philippine tech since we have exposure to the country’s most relevant startups.

We come in at pre-seed, whereas many other local funds usually come in at seed onwards. We act as our LPs’ entry point into the Filipino startup market.

While raising, what pushback did you face from LPs?

Their main concern is liquidity and exits.

There have been some exits, but usually small-scale M&A. The big question on everyone’s mind (including ours), is how we can convince LPs that the Philippines is a large, exciting, and valuable market for their investment.

And how do you do so?

We’re still early in our fund cycle and mostly focused on deployment. Once GCash IPOs (sometime next year), and later-stage companies like GrowSari, PayMongo, and Locad exit, proof that venture outcomes are possible here will materialize.

What do outsiders often misunderstand about the Filipino market?

First, many assume that the government is backwards or unhelpful. To some extent, that’s true. But “the government” isn’t a single monolith. There are different bodies within it, and some are more forward-looking and collaborative than others. In fintech, the central bank and the SEC are still catching up. They want to work with the private sector and startups through pilots, sandboxes, etc. The people within those departments are generally smart and well-intentioned.

Second, there’s a tendency to assume you can simply copy-paste foreign solutions. That has worked in some cases (Lazada and Grab are proof of such), but in many ways, the Philippines has different dynamics. We’re an archipelago composed of 7,000+ islands. Anything involving logistics and distribution demands reinvention, for example.

Third, the Filipino economy is dominated by conglomerates. Distribution really matters. But while these big families run the country’s major businesses, they are increasingly supportive of startups. They’re partnering rather than competing with them. You see groups like Gokongweis and the Ayalas not only starting venture arms but also sometimes acquiring startups. That’s generally positive for us because it provides potential distribution and exit pathways.

Given the Philippines’ consumer behavior and digitalization, is there a regional market you see as its most relevant comparison?

This is not an original take, but India is perhaps one of the most compelling proxies. There are a couple of reasons for this.

One is the large, young, consumer-led economy. Both economies are driven by domestic consumption and have rising middle classes eager to pay for convenience and digital services.

Second is the set of challenges. In India, a salient topic is DPI (Digital Public Infrastructure) and India Stack (India’s national DPI, comprised of open APIs allowing entities to deliver identity, payments, and data-sharing services). We’re working on a paper comparing the state of the Philippines’ digital infrastructure with India Stack. We’re aiming to offer recommendations on how we can get to where India is today across four layers: identity, payments, data, and consent.

Third, both countries have large unwieldy democracies, big BPO/services sectors, and populous diasporas. Many of our founders have come home after studying or working in the US, similar to the “sea turtle” phenomenon in China or returnees in India.

Fourthly, Indian conglomerates are also working with and acquiring startups. I don’t know as much about India’s corporate landscape, but I know that the likes of Reliance, Tata, etc, are deepening their interaction with the local startup scene. A similar trend can be observed in the Philippines.

Disclaimer: all internal company metrics shared in this article are claims from the interviewee. They have not been independently verified. Do your own due diligence.

The Realistic Optimist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice.