"Our biggest advantage and our biggest disadvantage is being Pakistani"

An exclusive interview with Kalsoom Lakhani, GP of i2i Ventures, a Pakistan-focused VC fund.

Speaker bio

Kalsoom is the co-founder & General Partner at i2i Ventures, an early-stage venture capital fund for Pakistan, and the country’s first female-founded VC fund, launched in 2019. i2i Ventures has invested in TelloTalk, Edkasa, CreditBook, Abhi, Oraan, Tazah, Truck it In, EZBike, Metric, Rider, DealCart, Safepay, Swag Kicks, and more.

Alongside i2i Ventures, Kalsoom is also the Founder of Invest2Innovate, i2i Ventures' sister entity, which she launched in 2011 to support and unleash the potential of young entrepreneurs in growth markets like Pakistan.

She has trained young entrepreneurs, changemakers, and civil society leaders in countries like Kosovo, Nepal, Cambodia, Ireland, Bangladesh, Ukraine, and Kazakhstan, and has spoken at numerous venues, including the World Economic Forum, Aspen Ideas Festival, U.S. Chamber of Commerce, U.S. State Department, the Global Entrepreneurship Summit, and SXSW. Kalsoom is currently a nonresident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council and recently served on the Board of the American Pakistan Foundation.

You’ve been involved in the Pakistani startup ecosystem for the past 10 years. What has changed?

The caliber of founders has reached new heights. The startups popping up in the country today are miles ahead of what they used to be a decade ago in terms of maturity, potential, and professionalization. I believe this is due to the confluence of two main factors: founder demographics and investor presence.

Founders in the ecosystem today tend to be a bit older than they were before, many of them sporting multiple years of professional experience at consulting firms, large corporates, or scaled-up regional startups such as Careem.

This evolution of the founder demographic coincided with the arrival of more relevant and adequate funding sources in the ecosystem. When I first arrived, most of the funding available came from what I like to call “vulture capital”, exploiting founders’ lack of options and experience to siphon unreasonable terms. The influx of more mature capital from international venture capital funds, as well as the launch of Pakistan-focused funds such as Zayn Capital, Indus Valley Ventures, Fatima Gobi Ventures, Sarmayacar, and i2i Ventures enabled the ecosystem to level up.

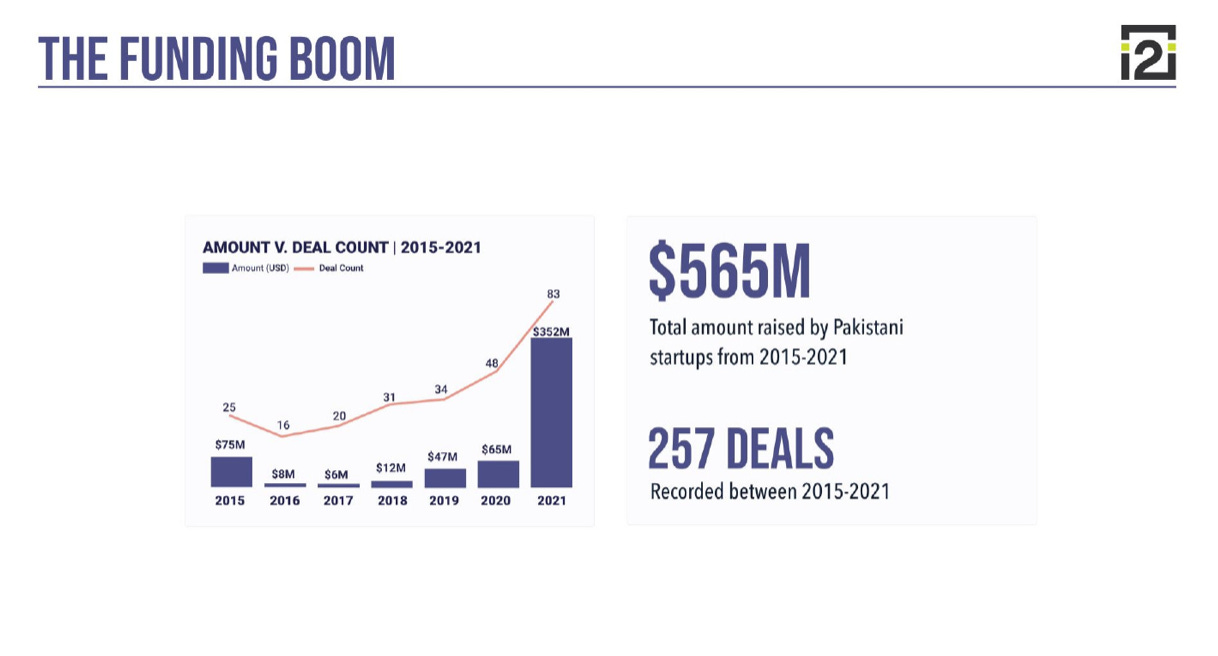

2021 was a landmark year for the Pakistani ecosystem in terms of funding ($50M in 2020 to $350M+ in 2021). What do you attribute that to?

The 2021 funding bonanza was a worldwide phenomenon. In emerging markets especially, startup funding levels jumped in virtually every region, from Africa to LATAM.

This global trend partly explains Pakistan’s 2021 funding levels. At the time, the country was also surfing on a positive macroeconomic wave, enticing Pakistani diaspora talent to come and start their companies back home, and Pakistanis abroad to invest in startups in the country.

From a purely practical standpoint, the pandemic made it acceptable to run due diligence on deals from afar. This bolstered the entry of foreign VCs into Pakistan, who could now invest halfway across the world through Zoom and WhatsApp. Low-interest rates also meant that those VCs had money to spend, and the Pakistani market represented a breath of fresh air from the overvalued US one.

Locally, the ecosystem was enabled by a couple of key governmental measures. In particular, the “holding company legislation”, which allowed Pakistani startups to raise money through a foreign entity, made raising from international investors much easier.

Was 2021 a net positive or a net negative for the ecosystem?

It’s more nuanced than that. That year undoubtedly leapfrogged the Pakistani ecosystem into a new dimension. The sheer amount of funding poured into local startups enabled them to recruit the best local talent, with many leaving their cozy FMCG jobs to embark on the startup gold rush. This influx of talent into the ecosystem is obviously a positive.

The talent equation also works the other way around: well-funded startups such as Airlift, Bazaar, and Retailo created a new generation of startup-trained, battle-tested potential founders and operators. Dastgyr, one of Pakistan’s most promising startups today, was founded by two ex-Airlift employees, for example.

Finally, massive 2021 rounds such as that same Airlift’s $85M Series B showed that building and scaling in Pakistan were possible. That mental component, the simple fact of seeing that it’s possible, is for me one of the most tangible positive effects of 2021.

That being said, 2021 did leave some bruises. Caught up in their funding fury, a lot of foreign investors invested in the market without adequate due diligence and ended up getting burned. It will be hard to convince those investors to return to Pakistan, especially now.

The hyper-competitive funding environment also pushed startup valuations to new heights, creating somewhat of a “2022 hangover” where Pakistani founders are going through the painful process of raising down rounds. The spectacular failure of some of the most funded startups during the period, including Airlift, and scandals such as YC-backed Tag’s legal troubles with the State Bank of Pakistan, did some damage to the ecosystem’s reputation.

From a more internal matters perspective, what do you think is the Pakistani ecosystem’s biggest advantage and disadvantage?

I might be biased in saying this, but I do truly think that Pakistani founders are a different breed. Operating in such a complicated and chaotic environment creates a certain type of resilience I haven’t seen in many other founder nationalities.

On the disadvantage part: one of the frustrating components of our ecosystem is that there’s a lot out of our control. Pakistan as a country has always had a bad reputation on the international scene. We’ve always had to be defensive about the market, and the speed with which foreign investors left the country post-2021 shows how fragile the credibility we built was.

In a globalized startup world, this negative international perception can be damaging. Legacy restrictions such as anti-money laundering laws make large flows of money in and out of Pakistan automatically suspicious. This doesn’t help our ecosystem. The widely relayed, internal political crisis happening right now definitely isn’t helping our case either.

Just as with many other emerging markets, foreign aid is strongly present in the Pakistani startup ecosystem. What’s your view on its impact?

I do have strong opinions about this topic. Let me start by saying that I do believe the “startup-support” programs put in place by foreign aid organizations generally have positive intentions. The results, however, are far from conclusive. We once received aid money to run an acceleration program at Invest2Innovate a number of years ago. This program had the worst outcomes, for multiple reasons.

First, the organization funding us only allowed the onboarding of startups that addressed maternal and child health, a worthy space but quite a niche. As a result of it being narrow, startups that applied for the program had to retrofit their business models to the aid organization’s KPIs, moving them away from a focus on their own commercial strategy. This created an absolutely disastrous situation: not a single one of the startups that went through that program survived afterward.

Such is the original sin of foreign aid, startup-support programs. They impose foreign aid KPIs on the companies they “support”, with little regard for what the market actually demands. This creates weak companies, hopping from grant to grant and award to award, with little to no commercial success. I know this frustration is shared amongst other VCs in young startup ecosystems, where foreign aid is omnipresent and pollutes the already limited local startup pool.

The conundrum lies in the fact that early-stage ecosystems often rely on foreign aid money to fund their first incubators, VCs, competitions, etc… This can durably penalize the ecosystem. But there are good examples – currently our team at Invest2Innovate is running a program with the World Bank under the Women’s Entrepreneurial Finance Initiative (We-Fi) called WeRaise to support women-led startups in Pakistan. The KPIs from the client are actually aligned with the companies’ commercial success since it’s laser-focused on shifting the status quo on women-led companies raising capital in Pakistan.

While this isn’t an “aid” organization per se, it’s a good example of how other aid organizations can be involved in early startup ecosystems, by becoming a piece of the funding value chain rather than imposing destructive anti-market KPIs on them.

From an outsider's perspective, one of the things Pakistan’s startup scene does extremely well is engaging its diaspora. What’s the secret sauce?

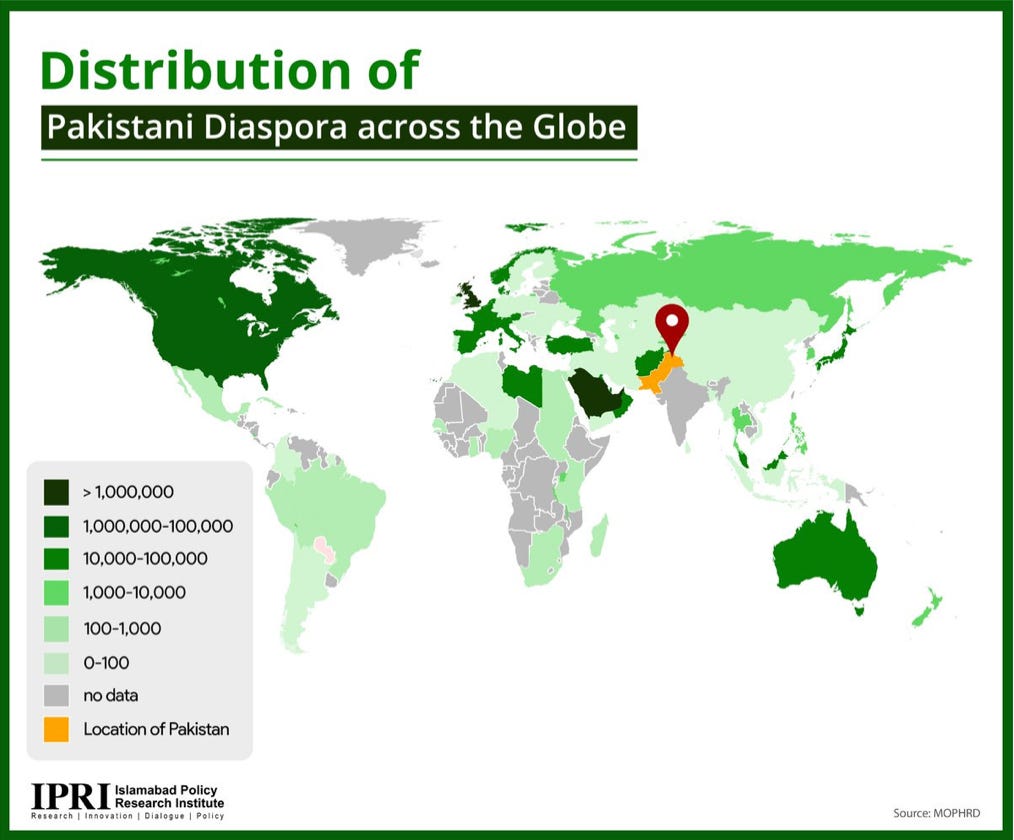

Pakistan has always had a very strong relationship with its diaspora, as evidenced by the important remittance volumes ($31B in 2021 alone). Pakistanis abroad are generally connected to their family back home, and it isn’t rare to see them funding charity projects. This symbiotic relationship between Pakistan and its diaspora isn’t an absolute anomaly, but not all ecosystems benefit from that baseline of existing diaspora engagement.

While the connection between the Pakistani diaspora and philanthropic giving isn’t new, the engagement with the startup space has really picked up in the past few years, propelled further by initiatives and communities like Paklaunch. There are so many Pakistanis involved in the technology sector in the U.S., Europe & MENA, and many had been looking to give back with their time & mentorship – as the ecosystem picked up, they also began to invest in startups in the country, and we’ve seen a number of angel networks and groups form in response to this.

How intertwined is the startup ecosystem and the country’s political situation? It seems that in the US, startups continue growing despite what’s going on at the White House.

The ecosystem has shown that it doesn’t develop and grow because of favorable political situations, but rather in spite of it. Pakistani startups represent a constantly flowing river while political turmoil represents rocks: the water always figures out a way to get around them.

The political situation does impact the ecosystem on a purely operational aspect. When a politician leads a protest and effectively shuts down a city, a logistics startup, for example, will obviously have a hard time operating.

I’ll also add that severe internal turmoil doesn’t help the international perception case we spoke about earlier. International headlines about political and economic instability doesn’t help in giving foreign investors the confidence to invest here.

What is the one public policy you would pass to unlock the ecosystem’s potential further?

I’d continue to improve policies that would ease the flow of money inside and outside of Pakistan – it’s such a challenge for investors and for startups alike right now, made all the more difficult because of our presence on the FATF list, etc. I’d also improve the overall tax regime for startups, given that it’s quite onerous to build a company in the market.

What are some overall areas of improvements the ecosystem should tend to in order to improve?

On the funding side, it is still hard for Pakistani founders to raise post Series A rounds without needing to tap into international money. We definitely have a dearth of growth capital as a whole, which is and will continue to stunt the overall growth of the ecosystem. There’s also a severe lack of working capital such as debt lines for capital-intensive startups (fintechs, etc..).

We need more diverse funding sources than venture capital – a lot of companies in Pakistan are not venture backable businesses, and that’s totally ok, but they need to be able to unlock other types of financing to grow their companies.

Overall, the ecosystem has definitely come a long way but still isn't as locally resilient as India for example. We need to build more strong, indigenous VCs and incubators to help the ecosystem thrive when the world turns away from us for one reason or another.

The Realistic Optimist is a weekly publication covering the globalized startup scene.