About the author

Philip Bahoshy is the founder of MAGNiTT, a leading venture capital data platform for emerging venture markets across the Middle East, Africa, Pakistan, Turkey and South East Asia.

Before founding MAGNiTT, Philip held a management consulting role at Oliver Wynman as well as an investment banking role at Barclays.

Philip holds a bachelor's degree from the London School of Economics and an MBA from INSEAD.

2023’s recap

Interest rates are the devil of venture capital.

A rise in interest rates ushers in a "venture crowding out effect": LPs’ cost of capital increases and risk free allocations, such as US government treasury bills, become more appealing. When interest rates fall, lending becomes cheaper and risk free assets lose their charm, leading LPs to put their money to work in venture.

In 2023, high interest rates put in place to control post-pandemic inflation were maintained. Mechanically, VC investments haven’t picked up, and are unlikely to before rates are cut again.

Funding numbers had shown surprising resilience in 2022 across the MENA (Middle East & North Africa) region, surpassing what was widely considered an already euphoric 2021. Yesteryear did a good job of taming any remaining velleities.

The numbers are unequivocal: MENA startups raised $2.67B in 2023, a 23% decline from the previous year. Other indicators, that is to say all indicators, are also in the red. Compared to 2022, the number of exits is down, the number of deals is down and the number of investors is down.

The region’s VC ailments are part of a broader epidemic. In 2023, the world’s startups raised 42% less than they did the year before.

2023 wasn’t a good year for MENA’s startup ecosystem. Was it for anyone?

Safe & sound

Thankfully, venture capital’s vicissitudes don’t alter MENA’s startup opportunity.

High interest rates don’t change the fact that the region is large (20+ countries), populated with a tech-savvy, youthful yet tech-underserved population with a wealth of engineering and tech talent. Select countries such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar, hold dry powder reserves that make Silicon Valley VCs salivate.

High interest rates don’t change the fact that MENA startups have shown clear exit potential, most notably Careem to Uber ($3.1B) and Souk to Amazon ($580M). They don’t change the fact that some of the region’s largest public financial institutions remain adamant on funding tomorrow’s local tech stars.

As we enter 2024, the very case for startups in MENA is as pertinent as ever. The technicalities that make those startups happen are what fluctuate.

The Saudi exception

For the first year since MAGNiTT started publishing yearly reports, Saudi Arabia emerged as the region’s most funded ecosystem. Two reasons explain this novelty, and why the Kingdom will likely retain its crown in 2024.

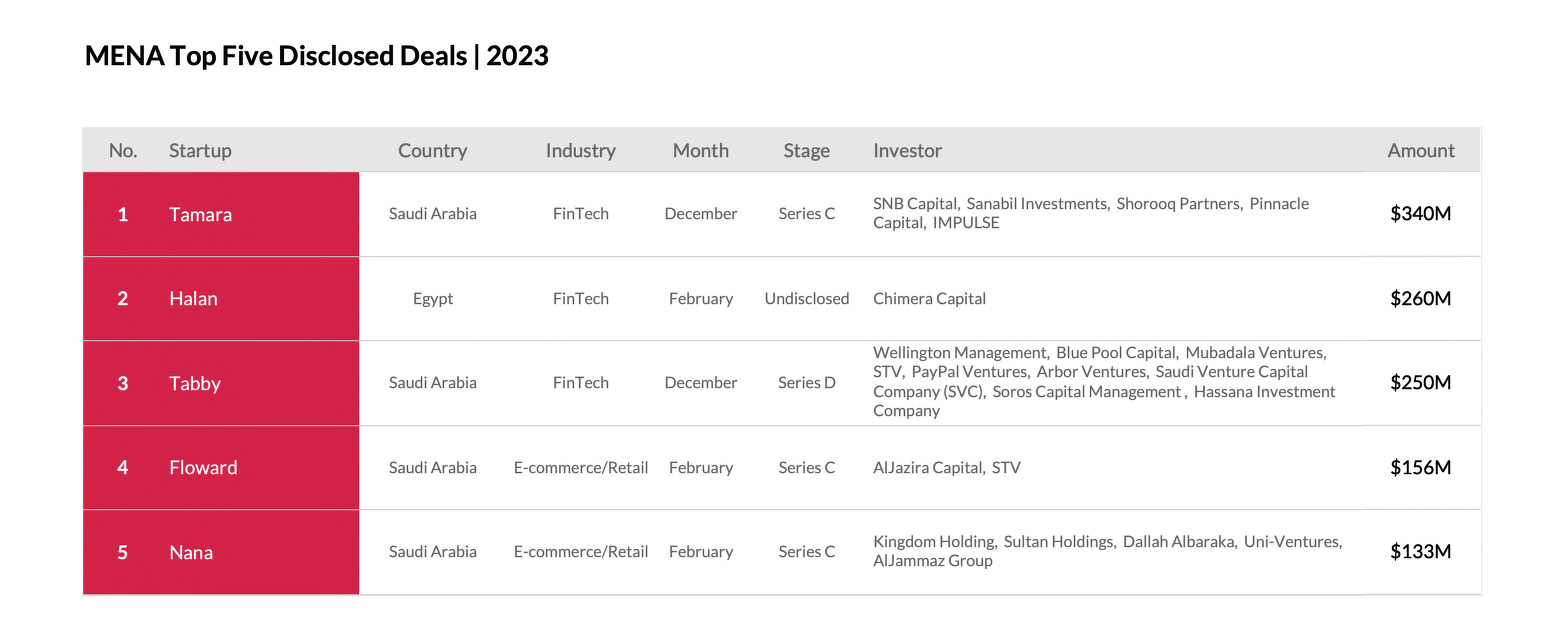

First, 2023 saw Saudi host numerous “mega-rounds” (funding rounds over $100M). Due to their disproportionate size, these types of rounds can make or break an ecosystem’s funding performance.

In 2023, MENA’s five largest rounds constituted 43% of the region’s total funding. Four of those rounds were led by Saudi-based companies. The remaining one was in Egypt.

Source: Magnitt FY 2023 MENA Venture Investment Summary

The second reason resides in the Saudi government’s Vision 2030, its economic diversification roadmap. The Vision 2030 plan includes a shift from commodity to knowledge-based productivity, the latter englobing generous support for local startups. Combined with its financial firepower, most notably the $700B+ Public Investment Fund (PIF), the Saudi government has substantially buoyed Saudi startups’ fundraising capacities.

Initiatives such as the the Saudi Venture Capital Company and the Jada fund of funds, designed to seed local VCs, make Saudi’s dominance of the MENA ecosystem predictable for the years to come.

New corridors

The MENA ecosystem seems to follow venture capital’s power law. More and more, a small amount of ecosystems are attracting all of the funding, all of the founders and all of the interest. These tend to be Saudi and the UAE, with Egypt trailing behind.

Regional governments tend to focus on their startup ecosystems at varying intensity, owing to the severity of current geopolitical and economic disruptions. This nonlinear government enthusiasm has been a challenge for many ecosystems. The ecosystems who come out on top are the ones where government support remains steadfast, come hell or high water.

As the dichotomy between ecosystems widens, local startups are rethinking their expansion strategies. Founders’ typical playbook used to entail becoming the regional leader in whatever sector they operated in. This is changing.

Put yourself in the shoes of a Saudi fintech founder, for example.

As funding tightens, you need to focus on the markets that will take your company to the next level. You could expand to neighboring GCC geographies. However, as has always been the challenge across the region, scale comes with new regulators and new paperwork. Many of these countries are a fraction of Saudi’s size, making you wonder if the juice is worth the squeeze.

Opportunistically, you could look at more populated countries across continents, including Turkey or Indonesia. The hurdles to setting up might be similar to a GCC country but consider this: Indonesia hosts a population size of close to 300M people. That is close to three times larger than MENA’s most populous country, Egypt with around 100M people.

Interestingly, Indonesia also hosts one of the largest Muslims populations in the world (over 200 million). The country has also already birthed tech unicorns such as Gojek and Tokopedia (who have since merged), meaning regulators have experience with the tech sector. For a Saudi startup, the case for an Indonesia expansion becomes potent.

Tighter funding conditions incites MENA startups to double-down on sane unit economics, but there’s no restrictions on geography. Anywhere is fair game as long as it serves the unit economics purpose. 2024 might be the year where we see these new corridors with Indonesia, Singapore and Turkey truly materializing.

Exits: needed and predicted

While exits dropped in 2023, 2024 might be the year they revive. Multiple factors inform that prediction.

As 2021-era valuations have dropped drastically, companies might become more attractive to potential buyers. This, of course, necessitates founders’ approval. But as early investors seek soft landings, some founders might not have a whole lot of choice. This will also play in with the increased startup interest shown by the region’s corporates. Prominent players such as E& come to mind, having financed a few exciting rounds in 2023 (Maxbyte, Airalo, Alma Health).

Some ecosystems, Saudi Arabia primarily, might see some of their superstar companies IPO locally. NOMU, a Saudi parallel equity market with lighter listing requirements, aims to serve that purpose.

Exits are undoubtedly what would most move the needle on MENA’s ecosystem. As the ecosystem enters its second decade of operation, these exits are needed to show investors that yes, betting on MENA startups can be lucrative. They are needed for founders and early employees to cash out, hopefully leading to a fresh cohort of regionally-skilled angel investors.

Conclusion

It is easy to equate drops in funding with an overall drop in startup potential. This is flawed reasoning, at least for MENA. Drops in funding in the present context are widely affected by macroeconomic incidences rather than a realization that “maybe startups just aren’t made for this region”.

The sectors that need MENA’s startups are numerous. Fintech, already the region’s most funded vertical, still has much to do. As the region digitizes, the opportunity for selling all types of goods on the internet (e-commerce) remains lush. The opportunities tech can bring to the region’s health and education system have barely scratched the surface. In a region that increasingly harbors global ambition, the need for local startups tackling the big problems in deeptech and sustainability is paramount.

Despite obvious and continuous challenges, the region’s ecosystem is charting its course. Similar to the argument made in this piece on the African VC scene, it tends to be hastily judged. Let’s remember that this ecosystem is a little over a decade old. It needs time and scrutiny to develop. Jumping to conclusions at the first sign of turbulence is short-sighted.

2023 was another year in the books, bringing its load of successes, surprises and failures. 2024 will be another year in the books, bringing with it the same trifecta.

For a startup ecosystem to develop, there’s no substitute for time.

The Realistic Optimist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice.