How Y-Combinator built a mafia in emerging markets

Part teacher part king-maker, Y-Combinator's absolute dominance in Africa, Asia and LATAM is a fascinating phenomenon.

YC’s genesis

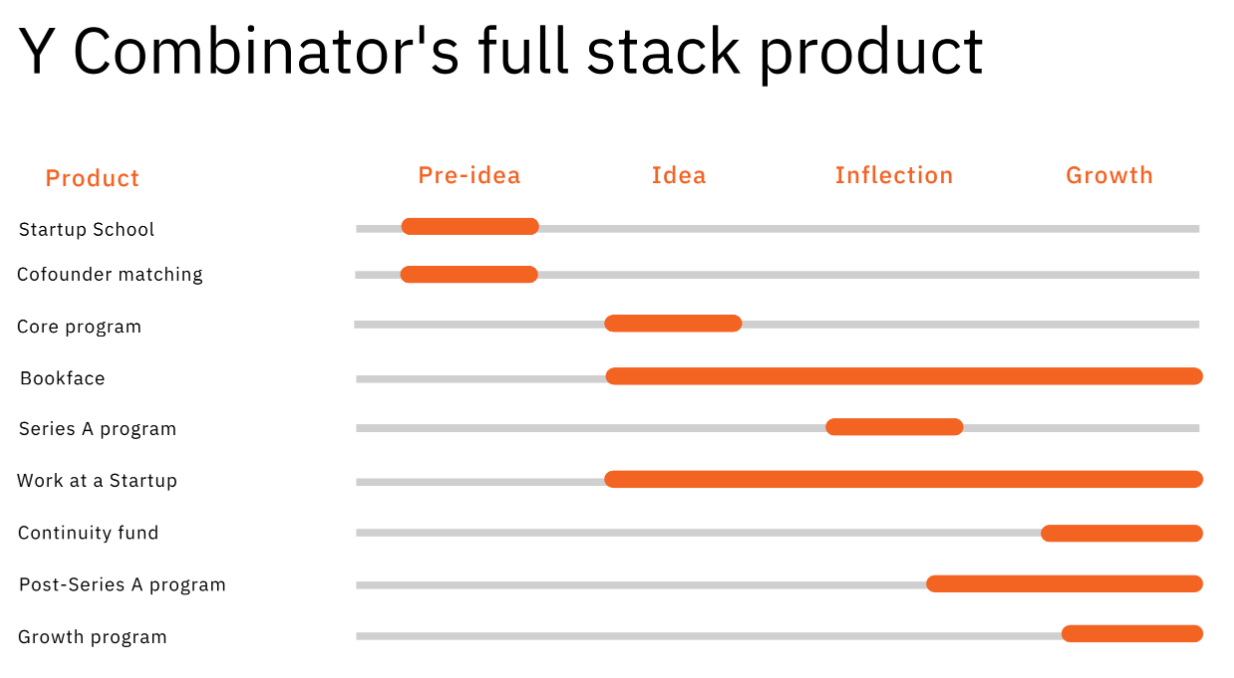

Y-Combinator, more commonly known as YC, is a startup incubator/accelerator/VC born from the minds of 4 co-founders (Paul Graham, Jessica Livingstone, Trevor Blackwell, and Robert Tappan-Morris) in 2005. Located in Mountain View, at the heart of Silicon Valley, it’s safe to say YC has become the indisputable protagonist in international start-up pop culture. Founders from Los Angeles, to Lagos, to Manila, view YC as the ‘Ivy League’ startup university that guarantees their company access to the world’s most potent network of investors, founders, and mentors. Over the years, YC has reinforced its position by expanding its services and essentially becoming an all-inclusive buffet for founders at all stages of growth.

YC’s biggest impact on the international startup world is not the companies it helped take off. Instead, it is the institutionalization and consolidation of startup best practices such as talking to your users, staying lean, do things that don’t scale, etc… YC’s teachings, distilled at length in their Youtube channel and Paul Graham’s blog, have the benefit of being clear, digestible, and actionable. They have inspired an entire generation of international founders, whose start-up building playbook is almost copy-pasted from the YC curriculum. YC’s hyper-pragmatic yet ambitious approach to start-up building gave birth to a generation of young founders bypassing the traditional corporate route to found start-ups instead.