Biography:

Sebastian Ruales is the co-founder of Bia Energy, a Colombian startup.

Bia enables businesses to access smarter energy consumption analytics, simplified billing, and more transparent access to renewables. In 2023, the company raised a $16.5M Series A round. It serves over 3,500 clients, in 250+ cities.

Prior to Bia, Sebastian was part of the founding team at Rappi, Colombia’s first unicorn.

Certain legislative changes ushered in Bia’s opportunity. How so?

One needs to understand where Bia sits in the energy value chain. We’re an energy retailer. Simply put: we’re the company that deals with clients directly. We install meters, handle billing, manage customer service, and ensure reliable consumption data.

For decades, Colombia’s energy incumbents did essentially nothing on the retail front. Customers received a bill, paid it, and never thought about it twice. One of our initial challenges was making Colombians understand that they could change their energy retailer in the first place.

Although Colombia opened the energy retail market to competition over 20 years ago, incumbents had no incentive to take action. Why disturb customers who—by inertia—kept paying on time?

That’s the gap Bia seized. We built a modern, customer-obsessed energy retailer that gives businesses real visibility: advanced analytics, smart digital billing, and renewable energy certificates. It’s the first time businesses in Colombia see energy as something they can manage, not just endure.

RO insights: the difference between 'energy' and 'electricity'

For readers new to the energy space, it’s important to differentiate between the terms “energy” and “electricity”.

Here’s how Romain Serres, co-founder of French energy startup Tilt Energy, explains how electricity is one way to use energy:

“A country has energy needs (for industry, mobility, appliances…) for which it taps multiple energy sources. These sources include fossil fuels (coal, gas, oil), as well as nuclear, renewables…

Within that energy consumption, France has seen a rise in electricity use, via consumer-led switches such as petrol-fueled to electric vehicles, or gas boilers to heat pumps. In 2023, electricity made up around 27% of France’s energy consumption. This is important in the fight against climate change, because the vast majority of electricity is produced by low-carbon energy sources (in France, that’s majority nuclear, followed by renewables).”

Excerpt from Tilt: optimizing France’s electricity grid, originally published in The Realistic Optimist

Bia buys energy, which it resells to customers. How does “buying energy” work?

Energy procurement is a complex science. Energy is non-fungible — it can’t be stored or moved easily.

The hardest part is balancing. Bia buys energy in bulk. If customers consume more than expected, we buy the difference on the spot market. If they consume less, we sell the excess on the spot market.

To manage this intelligently, we built an internal energy trading operation — a sophisticated engine powered by AI models, forecasting systems, and our own software suite (OliBia). The breadth of the data we use is vast. For example, we get data from the ocean floor’s soil to help us predict if it’ll rain or not. Knowing this helps us predict the price of hydro-electric power.

We typically buy slightly less than projected consumption, expecting to acquire around 10% on the spot market.

We also diversify suppliers: no single supplier accounts for more than 12% of our procurement.

This trading intelligence is becoming a product in itself. Similar to how Octopus Energy built Kraken, OliBia has the potential to become a SaaS platform for other energy utilities — a new frontier we’re actively exploring.

Changing energy retailer is heavier than trying a new food-delivery app. How did you get started?

The first barrier was awareness. Most people didn’t know switching energy retailer was even allowed.

From day one, we decided Bia would look and operate like a large, institutional energy company — not a hype startup. Before launching, we built a brand that felt solid, credible, and inevitable. We ran Deloitte audits early to signal discipline and long-term vision.

To acquire early customers, we leveraged personal relationships. I convinced a restaurant owner I knew. A friend’s father, a banker, switched his bank’s energy retailer to Bia. I convinced my former employer, Rappi, to switch.

These early logos became proof points that eased outbound sales.

You emphasize including Bia electricians in the company culture. Why and how?

Every time a client joins Bia, our electricians install our smart meter — they are our frontline. Their professionalism defines first impressions of Bia.

That’s why our electricians are full-time Bia employees. They embody the company’s values: excellence, empathy, discipline. We create a culture where they feel respected, included, and part of something bigger. We want them to wear the Bia jersey with as much pride as they would a football team’s.

Treating blue-collar workers with dignity and respect contributes to greater well-being and stability at home, which can even correlate with lower instances of issues such as domestic violence.

RO insights: internalizing blue-collar workers

For startups dealing with physical installations, blue-collar labor can be outsourced or internalized. Internalization can be more expensive at first, but better customer service, experience control, and speed can generate higher ROI.

Here’s how Raffaele Sertorio, co-founder of Mexican solar panel startup Niko, explains how they mixed both:

“[Our biggest challenge is] finding high-quality solar installers to install the panels we sell. This industry is still new in Mexico, so the corresponding talent pool is still thin.

We’ve decided not to rely on the limited number of companies offering such services (they prioritize their bigger clients over us) and have started building our own internal payroll of Niko technicians. We can still outsource “blue-collar” functions (ie: picking up the solar panels, physically installing them) but we need a Niko engineer to oversee the entire process.”

Excerpt from Niko: scaling solar panels in Mexico, originally published in The Realistic Optimist

How does Bia make money today?

First, we buy energy for cheaper than what we resell it for. We increase these margins by tapping into the real-time consumption data we gather, which enables us to procure more efficiently.

Second, we charge a licensing fee for the analytics software we provide.

Third, Bia helps clients install capacitor banks (which make energy consumption more efficient) and revenue share on the resulting savings in energy costs.

Lastly, we sell a “Bia Monitor” product for larger clients, giving them a granular view of energy consumption per factory zone, specific machines, etc.

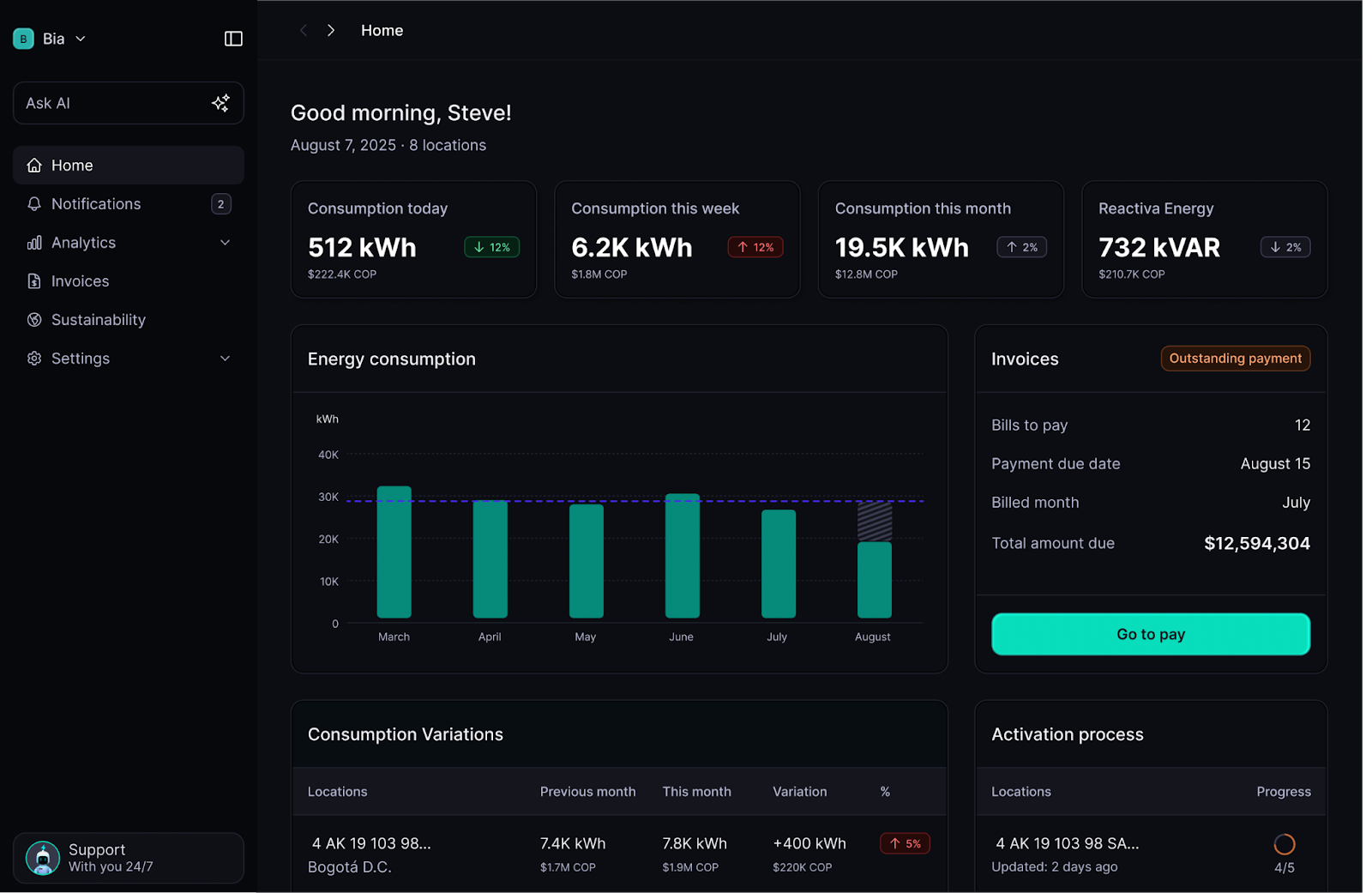

Bia’s analytics dashboard (English version)

Where will Bia be expanding, product-wise?

The smart meter we install is a Trojan Horse. It gives us real-time visibility into clients’ operations, yielding actionable insights. For example, we could recommend a client a specific air conditioning system that would be better suited to their energy consumption. We could then revenue-share with the air conditioning company whose product we recommended.

Our real-time energy data operates as a foundational infrastructure asset. It enables entirely new verticals such as efficiency tools, embedded financing, and equipment partnerships, positioning Bia as a core operating system for our clients.

The hard part about this business is maintaining focus. The energy industry is so intricate that we could do a thousand different things. To contain ourselves, I use a framework to strategize product expansion: Growth = Competitiveness × Value Proposition.

To be more competitive as retailers, we need lower prices. To lower prices, we need to control the origin of our energy. That leads to our next phase.

So Bia will start producing its own energy?

We’re already heading there.

We serve blue-chip clients — Coca-Cola, Ikea, Starbucks, Burger King — and their invoices are highly reliable (ie: it’s highly unlikely that these companies won’t pay their energy bill). We leverage those receivables as collateral to obtain long-term credit lines that allow us to finance, build, and own renewable energy projects, especially solar and hydro.

These projects often struggle to find financing early on. Because we trust our invoices and know our clients, we can unlock that financing ourselves.

Financing and thus owning energy generation infrastructure lets us produce our own energy without requiring CAPEX from day one. It deepens our moat and enhances price competitiveness.

What role do renewables play in the whole Bia operation?

Most electricity in Colombia is powered by renewable sources, especially hydro. Fossil fuels are used to compensate, when a drought reduces the amount of energy hydro generates for example.

We provide clients with renewable energy certificates, stored on the blockchain. This is useful for clients who then show their green energy-conscious boards or shareholders.

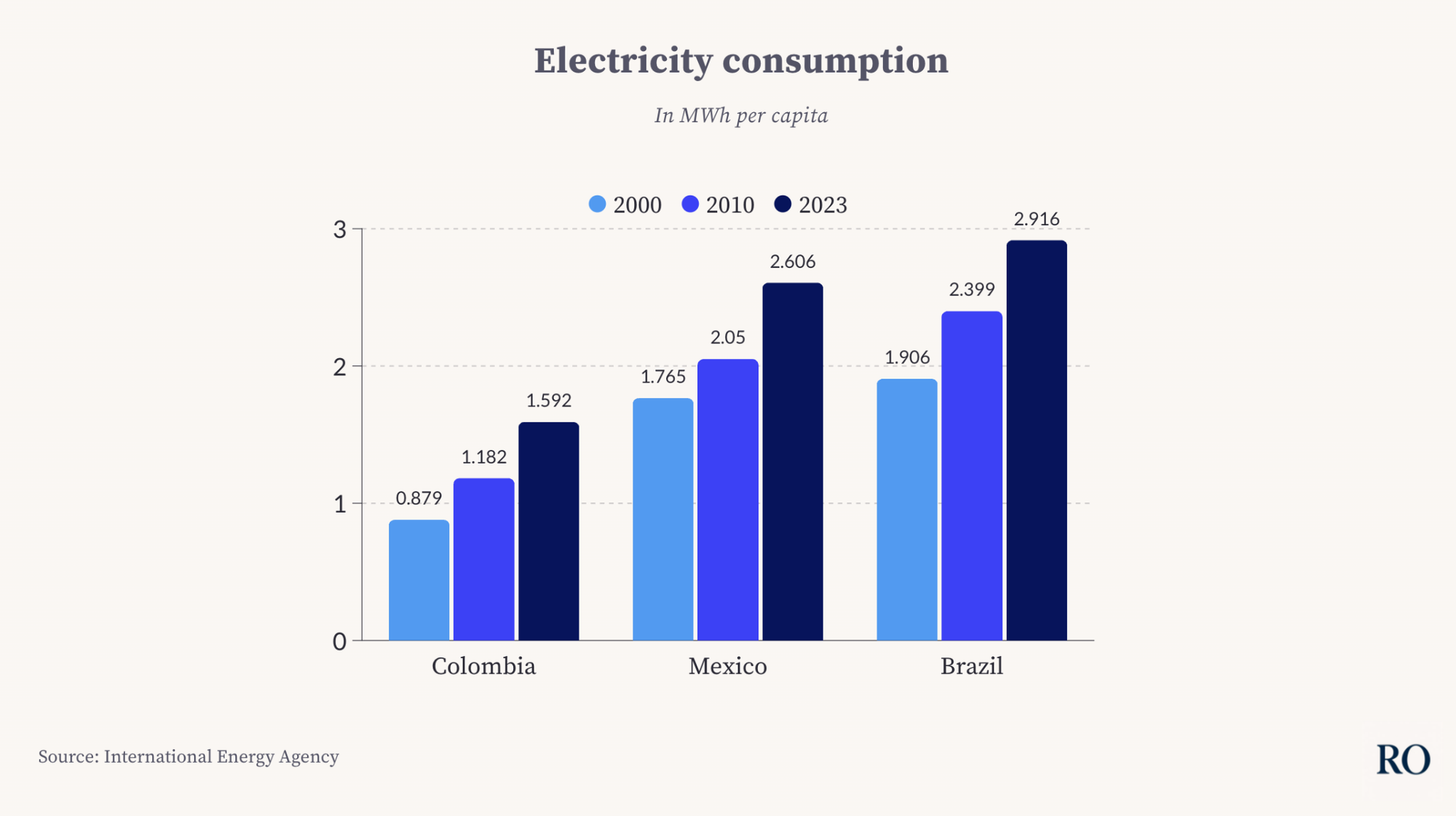

Source: International Energy Agency (for Colombia, Mexico, Brazil)

Regulatory-speaking, what’s the hardest part about this business?

We approach regulation differently than most startups. For us, it’s table stakes. We simply cannot mess up. We won’t be allowed to play if we break the rules. That being said, we have to be smart, not docile.

The challenge isn’t about a piece of regulation specifically. It’s more about the way we approach regulation as a company. We’ve had to develop our own fangs.

For example: when a client switches to Bia, they ask their old energy retailer to come uninstall their meter. Obviously, incumbent retailers would conveniently never be available to come uninstall the meter. We used to play nice and wait for them. Now we don’t. If the incumbent does not arrive within the established timeframe, we proceed with the installation (always in full regulatory compliance) to ensure our customers are not blocked by preventable delays.

We’ve also taken a more proactive approach to regulation. We try to constructively co-build good regulation alongside public officials.

RO insights: regulated industry = automatic moat

If startups can break into a regulated industry, they enjoy an immediate moat thanks to higher barriers to entry. A regulated industry often means said industry is essential for a country, emphasizing its staying power.

Here’s how Romain Serres, co-founder of French startup Tilt Energy, again:

“We operate in a highly-regulated industry. This is exciting. The more an industry is regulated, the higher impact it has on a country. This means it’s an industry worth improving.

Since it’s regulated, we’re at the whims of politics. For example, the price RTE (ED: a French government agency) pays out for demand response schemes fell due to a governmental decision. Since we take a cut of those payouts, it hits our revenues.

This is another reason we’re sector-agnostic. It’s practical to hopscotch between different client personas, as one might lose in pertinence following a regulatory decision. Being attached to only one would be dangerous.

We’ve had to develop regulatory savviness early. As a startup, you can be extremely early in your space and bulldozer your way to create new regulation (like Uber did). But we’re the opposite: we’ve had to take regulation very seriously, very early because we simply cannot operate outside of it.”

Excerpt from Tilt: optimizing France’s electricity grid, originally published in The Realistic Optimist

What’s been your biggest strategic mistake?

Nothing structurally dramatic, but there are a few things we could’ve done differently.

First, I failed to recognize the complexity of Bia’s billing.

Every city in Colombia has different taxes on energy consumption. If you’re in the agro industry you might get specific discounts for instance. The number of exceptions goes on endlessly.

In Bia’s early days, we’d end up with tons of billing errors that we had to redo from scratch, yielding unhappy customers… We’ve fixed this and our billing product is one of our strong suits, but we should’ve invested in it earlier.

Second, on the regulatory-side, we should’ve developed those fangs earlier. We should’ve behaved as the large energy retailer we projected ourselves as rather than the new polite kid on the block.

Third, there’s some better energy purchasing deals we could’ve made that would’ve saved us money.

Other than that, our pitch deck has been almost the same since our seed round. We haven’t undergone any major pivots.

What’s been your best and worst day as a founder?

We divide work in 3 seasons of 4 months. These seasons are divided between planning, execution, and reviewing results. The end of those seasons are great fun: each team presents the progress they’ve made, and they’re able to witness that every other team pulled their weight.

The worst days are days where we let people go. The person should always grow into the size of the shirt we made for them, not the opposite. Maintaining intense high-standards means we are forced to let go of team members who can’t hold that cadence.

It’s a culturally difficult thing to do. We’re Latin, we’re warm people, we create deep relationships. You make friends with these people, you have them over to dinner, you meet their families. The process is even worse if they love Bia and feel at home in the culture we fostered. Unfortunately, I have to go through this painful process every three months.

What do foreign investors misunderstand about Colombia’s startup scene?

I’ll extend your question to encapsulate LATAM’s ecosystem more broadly.Many investors fail to discern the difference between startups founded pre-2021 and post-2021.

2021 was the epitome of crazy valuations, oversized fundraising rounds… Founders that launched their startups after that period are a different breed. They don’t approach company building the same way. They’re focused on profitability, building in the “real” economy… Bia is part of this new generation of companies, shaped by discipline, realistic valuations and a focus on sustainable growth.

Investors might willfully blind themselves by only referring to the failure of pre-2021 startups, and miss out on this new crop of extremely performant startups.

The second thing, for US investors specifically, is that many LATAM startups are solving core infrastructure problems (access to finance, energy, health).

Of course, investing in AI startups in the US has tremendous potential. But LATAM startups like Bia aren’t riding a wave. We’re piecing together entire industries with our own tech. Since those industries aren’t going anywhere (especially energy, which is set to grow thanks to EVs, AI…), our competitive advantages will compound.

Lastly, a lot of investors worry about the lack of liquidity. I honestly believe that if they invest in companies that are reinventing industries, taking market share, producing revenue, and satisfying clients, liquidity will follow.

Investors should focus on that rather than trying to find “benchmarks” of similar, VC-backed exits in LATAM. The ecosystem is so young that many startups (such as us) are simply the first to do it. You won’t find a satisfactory local benchmark pool.

RO insights: the "new breed" of LATAM founders

The brutal market reversal post-2021 scared investors, but founders as well. As Sebastian mentioned, this new “breed” of founders are better equipped.

Here’s how Juan Pablo Ortega, co-founder of Colombian startup Yuno, explains:

“We owe a lot to previous generations of LATAM founders. They are the ones that built up to the 2021 euphoria. Pre-2021, LATAM founders lived in a scarcity mindset: local investors weren’t interested in VC, so founders scrambled for any foreign VC deal they could get. If Sequoia wanted to invest, you took the deal, even if the terms were iffy.

Many founders (myself included) worked at these startups. By observing, we became more astute on fundraising. The previous generation of founders also did the grunt work of opening up investor networks, both local and foreign. The “next-gen” founders that popped out of these startups (ie: “mafias”) have four main advantages.

First, they’re pickier on fundraising. They’ve seen what bad investors and bad terms can do to a company. They understand VC unit economics better.

Second, foreign investor networks have been built out. They have optionality, which turns them from beggars to choosers. This helps with the first point.

Third, they have easier access to talent. Not only do they have operating experience themselves, but their past experiences have widened the pool of local operators they know and can recruit. They’ve also gained recruiting know-how, essential in avoiding costly mistakes.

Fourth, they know more local angel investors. Many of them are friends, ex-colleagues or just professional connections that had a nice financial exit from their previous startup experience. This derisks their own startup launches and helps them move faster.”

Excerpt from LATAM founders are maturing, originally published in The Realistic Optimist

Disclaimer: all internal company metrics shared in this article are claims from the interviewee. They have not been independently verified. Do your own due diligence.

The Realistic Optimist’s work is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as legal, business, investment, or tax advice.